Flywheels, Subscriptions, and Sleep

It’s time to talk to your Tween about Netflix’s business model

Someone didn’t sleep very well last night.

In so many families that had to rely on screens for school and play during the lockdown, children have figured out how to access more apps and browsers and figure out workarounds to the pre-COVID19 boundaries that were carefully set by their parents and caregivers.

This behavior might be hidden to you. Here’s how you notice. You check the screen time report and notice some late-night binge-watching activities for a smartphone your child uses, that you tucked away in another room, far away from their bedroom.

Ok, the “you” in this story is me.

It is time to talk to my tween about the business model of Netflix.

The N in FAANG, the superpower high flying tech companies that just keep growing and growing in value. (Facebook Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google).

I thought Netflix was a little safer.

Netflix attracts far fewer scandals than the rest of the pack because they seem to have the better business model.

So clean, so clear. Subscription! An honest transaction that shows up on your credit card statement. No ads. No data secretly traded to marketing companies. No chance to tangle with democracies or foment trolls or hate.

Their growth has been phenomenal this year. Subscribers were up. Of course, they were. There was nothing else for anyone to do. In the time from April-June, they added 10 MM reaching 193 MM subscribers. Revenue is at $6.1 BN, 25% up year-over-year.

They report these figures in an earnings statement and call last week, which were both cautious reports from the company. Netflix appointed Co-CEO Ted Sarandos, the content king of Netflix, to share the reigns with long time CEO Reed Hastings.

Netflix lowered its estimates for the coming third quarter.

"We live in uncertain times,” their shareholder letter began. Indeed. Growth has likely “pulled forward some demand from the second half of the year.” Meaning - if you were one of the last hold-outs without a Netflix account, a global pandemic was the perfect opportunity to sign up. So they don’t expect that to continue. Only 2.5 MM more subscribers are expected next quarter.

But Netflix likely doesn’t have to worry too much because they make money in the long run, with the same key performance indicator that is messing with my tween’s sleep schedule: the retention rate.

Retention is the percentage of subscribers that do not cancel Netflix. It’s a key metric for any subscription company.

Netflix makes money by keeping us around. Netflix does not report its retention rate but analysts and investors that look at credit card data estimate a rate of between 90-95%.

I think I got my first Netflix account in 2001. While they’ve changed their prices over the years let’s assume an average of $12 over 19 years, that is $2736 over what’s called a lifetime value - and there is more life yet to live. The company’s cash flows are super predictable, giving them an ability to raise debt and generate a high-value stock price because once Netflix lands a customer, they are likely to stay.

In order to keep us around, we have to feel a pull to keep watching, or the pull of our extended family members and friends on our Netflix plan to keep asking for that updated password. Netflix has to keep us “engaged.”

There’s that word that we have grown to love and hate when it comes to the rest of the FAANG. The business models of advertising and one-day delivery e-commerce are often blamed for the negative consequences that arise from a singular focus on engagement.

“Facebook should shift to subscription and get rid of ads,” say, armchair strategists and ethicists, as if the business model of advertising is the thing that is bad, not the decisions of the leaders in these companies.

Let’s take a look under the hood at Netflix, one of the largest subscription companies in the world.

The biggest digital business model innovators move in mysterious ways. The are combiners. They combine and recombine business models in circular loops - like flywheels.

A flywheel is a rotating mechanical device that is used to store kinetic rotational energy.

Flywheels smooth the power output of an energy source.

In research for the book Good to Great, author Jim Collins observed that great companies generate the “flywheel effect”:

“You get the flywheel to turn one entire turn. You don’t stop. You keep pushing. The flywheel moves a bit faster. Two turns… then four… then eight… they flywheel builds momentum… sixteen… thirty-two… moving faster … a thousand … ten thousand … a hundred thousand… Then at some point — breakthrough! The flywheel flies forward with almost unstoppable momentum.”

A cool flywheel making paperclips found on Reddit:

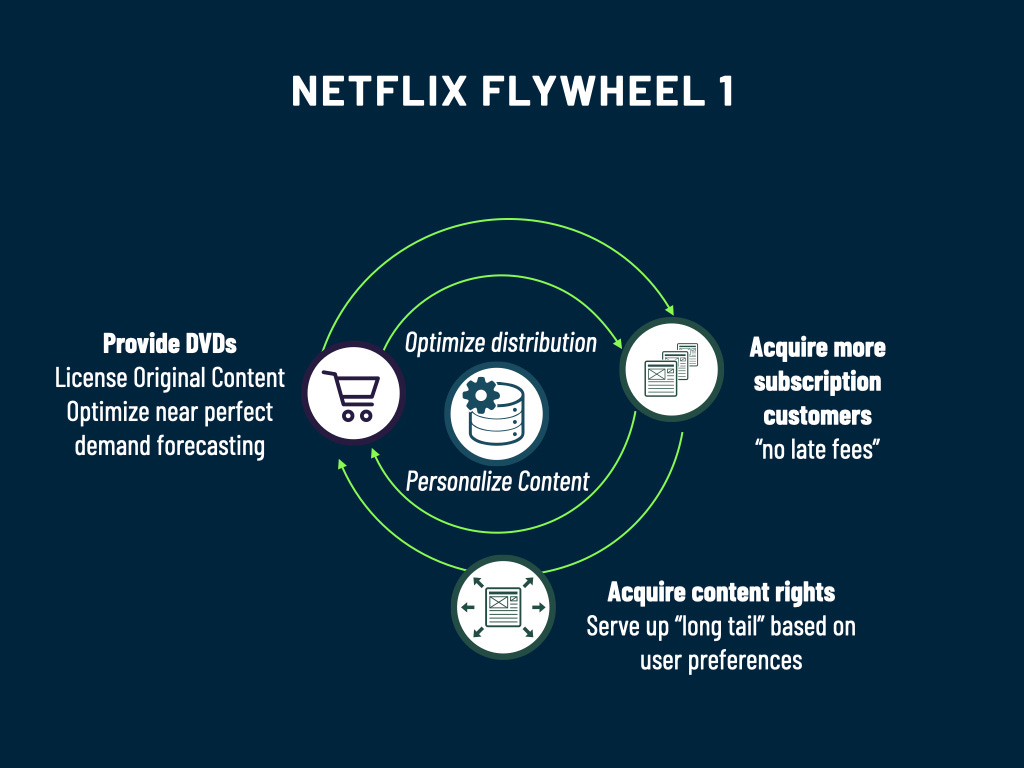

Here is Netflix’s flywheel in three parts.

Flywheel 1: Licensed content, DVDs by Mail, Personalization

Netflix started with a VHS experiment that didn’t pass the mail test. They genuinely got lucky with the rapid adoption of DVD players in the first few years of their launch. The provided DVD rentals and the flywheel started to turn.

Netflix shifted to subscription-based services which gave the company more predictability, and they invested more in its technology backbone.

The flywheel got stronger as Netflix shifted to optimize the experience. Netflix invested in a data analysis engine that helped customers start to sample a long backlog of content they might have missed - those indie films and foreign films that never made their way to Blockbuster. Coined the “long tail” by Chris Anderson of Wired Magazine, the early belief of Internet pundits was that we would move away from big hit blockbuster content and start to develop hyper-individualized preferences.

Content Library: Licensed, particularly focused on “indie” and harder-to-find titles, not dependent on blockbusters like Blockbuster.

Market: Small but fast-growing focused on film buffs and growing fast following DVD player adoption curves.

Effect on Customer Sleep Cycles: Limited. Even DVD players that could hold 5 disks at a time-limited the chance that you would sit on your couch forever. Although Portlandia has an excellent parody of DVD abuse that shows the dangers of consuming an entire series of Battlestar Galactica in one sititng.*

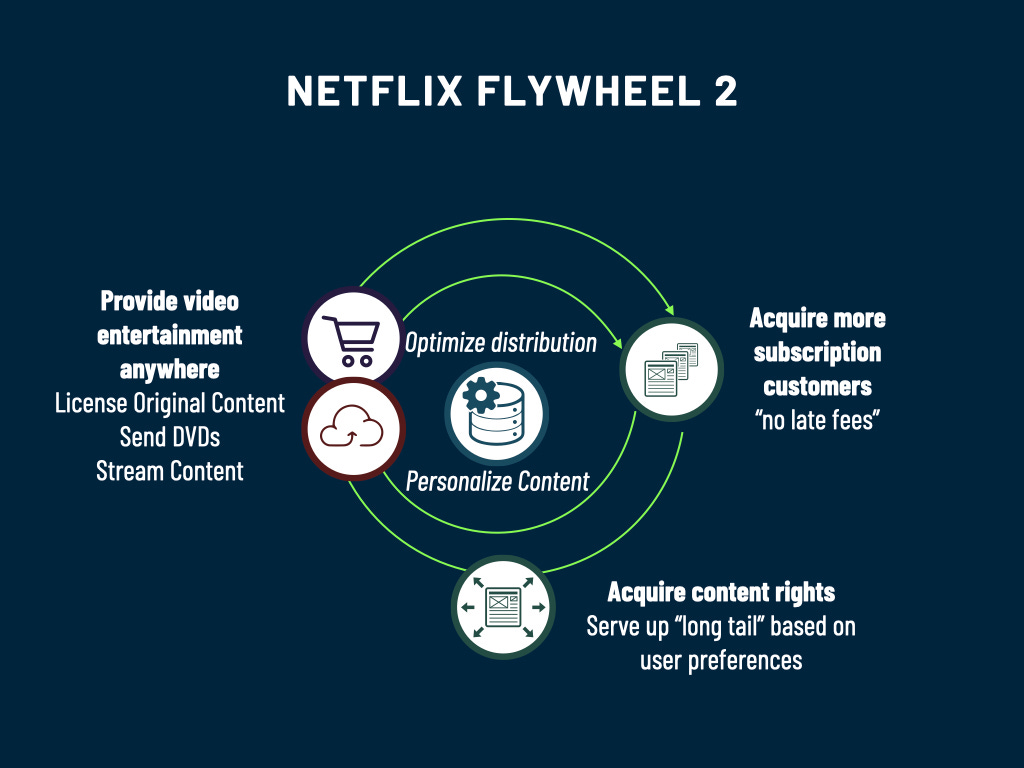

Flywheel 2: Streaming Pivot

The company managed a pivot in the mid-2000s as they shifted to streaming. Netflix flubbed the launch in 2007 first by naming it Qwikster and second through a poorly thought through tiered pricing strategy, splitting the service in two. There is even an SNL skit mocking the fumble.

But the company recovered and the flywheel began to turn again, building more momentum and increasing the growth rate and retention rate of customers.

Big Hollywood studios did not yet see Netflix as a major threat, particularly with that early streaming misstep, and they continued to license content to Netflix. Subscribers to Netflix began to find hidden gems in the content libraries and reviving long-form series like Breaking Bad, making them hits beyond the original network releases.

Simultaneously Blockbuster went bankrupt, a combination of poorly managed debt, and activist investors impatient with their out-of-kilter flywheel as they tried to simultaneously double down on their retail strategy while trying to also develop their own digital version.

Content Library: Netflix acquired the rights to Vongo, a failed broadband service of Starz/Liberty Media, and instantly offered 2500 new titles without having to tango with studios.

Market: Growing, Following broadband adoption curves.

Effect on Sleep Cycles: Moderate. Streaming was OK but sometimes a little glitchy.

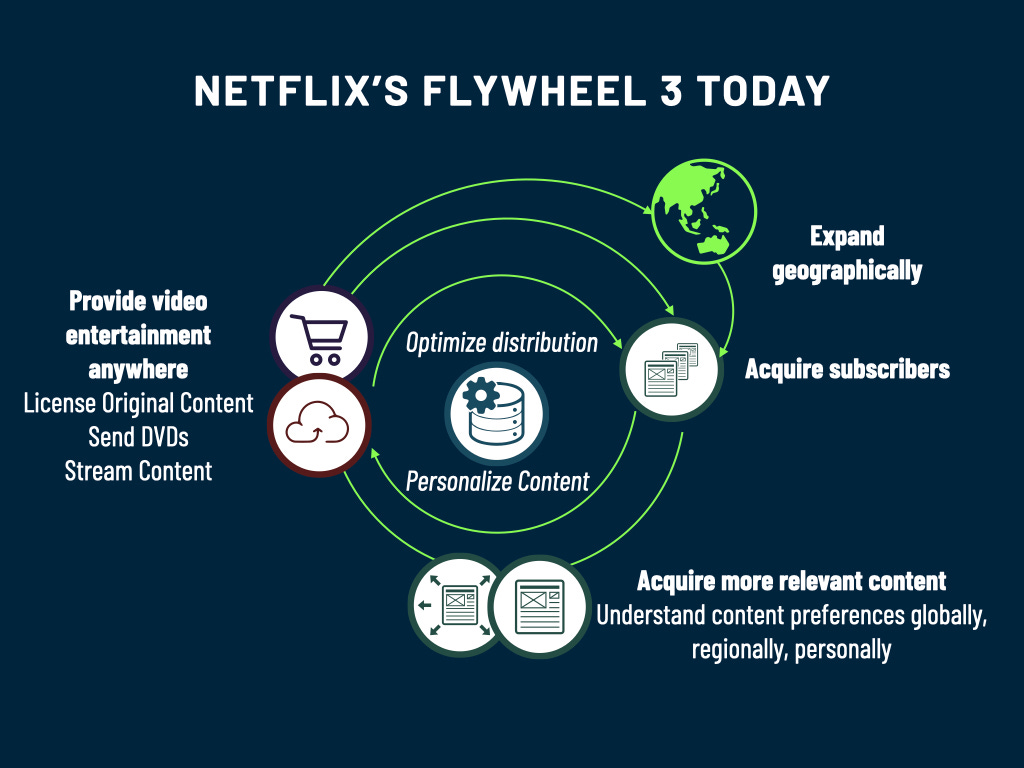

Flywheel 3: Original Content, Hollywood

Major studios finally started to worry about Netflix, and the company intentionally began to develop its own content to protect its position.

In 2011 Sarandos bid a huge amount of money to acquire rights to House of Cards and then making the decision to release the entire first season all at once on Friday, Feb 1, 2013. I remember because we didn’t do much else that weekend but watch House of Cards, and we didn’t get much sleep.

The major business model innovation was not subscription. It was subscription + streaming + original content production + ambition to be the largest media company on earth + global domination + ability to raise debt and price their equity at a higher value than any other Hollywood studio. It will be hard for the newer streaming services to catch up because of Netflix’s back catalog, optimized streaming, and discovery, and sheer scale.

Now every day two to three shows are launched on Netflix per day and they are one of the largest studios in the business.

They are the third-largest spender on content in 2019 and while Disney and Comcast have to share the distribution with TV and movies and theaters and such, Netflix has one and only one channel, a more precise flywheel:

Disney. $27.8 billion

Comcast. $15.4 billion

Netflix. $15.0 billion

ViacomCBS. $15.0 billion

AT&T. $14.2 billion

Amazon. $6.5 billion

Apple. $6.0 billion

FOX. $5.7 billion

Source: Variety

Netflix now has 1,600 original shows (compared to Peacock’s 8) and a large backlog ready to release, so the pandemic may not result in a major lull in the constant drip of new shows. Netflix crafted a completely new form of high-quality entertainment, shifting the center of quality in the business from movies to streaming series.

Their domination is global, but not in that American-cultural-hegemony way. We all get to share in the bounty binge-watching shows like Elite and Money Heist from Spain, Sacred Games from India, and Girl/Haji, a British/Japanese series.

Content Library: Original content, series, global

Market: Global almost everywhere

Effect on Sleep Cycles: Sleep is the enemy of Netflix

Back to my tween.

Netflix posits that sleep is their competition.

“You get a show or a movie you’re really dying to watch, and you end up staying up late at night, so we actually compete with sleep,” said now co-CEO Reed Hastings back in 2017.

It was a clever way to reframe the competitive landscape away from Amazon Prime streaming, HBO’s apps, Hulu, and then all of the services that are later to the party: the OK Apple TV+, the ad-based Peacock, and the laughable Quibi.

Competing for sleep.

The total addressable market for Netflix seems to be the failings of the human body and our inefficient need for rest.

To complete this public service announcement, ask your tween or teen: what do you notice about how Netflix is designed that led you to stay up until 3 in the morning?

The ingredients:

A show with all of your favorite personal elements. For my tween: a show with sci-fi combined with romance, superpowers, and a world-saving plot.

High tension cliffhangers in the last 2 minutes of each episode.

“Next episode” button with a disappearing gradient making you feel like you’re going to miss your chance.

“Skip the recap” button to find out what happens next as soon as possible.

“More like these” options when you’re all done with the binge.

Then the feeling:

How do you feel after a night lost to binge-watching?

Answer: meh. drained. yuck. not happy.

What do we know for certain? Reed Hastings knows.

“The things we are certain of is the Internet is growing. It’s a bigger part of people’s lives, thankfully. And people want entertainment. They want to be able to escape and connect, whether times are difficult or joyous.”

Sounds nice, Reed and your co-CEO Ted.

But please, dear Ted and Reed, please don’t compete with our sleep. Be the better FAANG.

Deeper Dives / Can’t Sleep?

Excellent podcast on Netflix’s history, Land of the Giants, is being produced one-at-a-time on Vox.

There’s a sub-Reddit for Mechanical Gifs if you are mesmerized by flywheels.

The “sleep is our competition” claim by Reed Hastings.

SNL mocking the Netflix apology after the flubbed streaming launch of Qwikster.

*Stream the Portlandia clip mocking obsessive series watching here’s a taste on YouTube but you can binge-watch the whole segment called One Moore Episode and the entire series on Netflix.